Phantom Bodies and Simulated Tactility

In the previous chapters, the body appeared primarily as an active participant in interaction—touching, moving, responding—whereas here it becomes both image and material. In the selected works, artists recreate bodies anew: reconstructed, artificial, assembled from silicone, wax, fabric, metal. They appear alive, though no life is present within them. It is in this paradox—presence without the one who is present—that phantom tactility emerges.

The viewer responds to the artificial as if it were alive, sensing the familiar qualities of skin, its fragments, softness, warmth, or vulnerability, even when the material itself is inert. These works engage the memory of the body: bodily sensitivity continues to exist without physical contact. Tactility shifts into the imagined, turning into a field of sensory illusions and empathic projections.

Contemporary artists do not imitate the body literally—they explore its capacity to become metaphor, vessel, and a form of experience. Their work shows how the body continues to live within material: compressing, decaying, flowing. In this, a new corporeality takes shape—hybrid, artificial, yet emotionally truthful. This body does not require touch, because it becomes touch itself—an image that evokes a response.

The Body in Transformation

In contemporary art, the body often appears at the moment of deformation, disintegration, or change. Artists abandon the fixed image of the human, approaching corporeality as a state. Here, transformation is understood not as a metamorphosis of form but as an experience: the body is felt as a fluid material capable of changing while still retaining its sensorial nature.

From the soft organic forms of Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois to the bodily shells of Francesco Albano and Berlinde De Bruyckere, these works explore how the body can be fragile, vulnerable, and still deeply resonant. They capture the moment of becoming, when the material turns emotional, and the skin becomes the boundary between the inner and the outer.

Nue couchée, 1969–1970 — Dorothea Tanning

Tanning’s soft sculpture balances between body and object, between movement and stillness. The smooth, sewn fabric form, stuffed with wool, resembles a creature or a tree trunk with severed branches.

Tanning moves away from literal representation and creates an organic shell in which the living is sensed through details and contours. There is sensuality without eroticism; presence without a concrete human figure. Tanning shows how form can be bodily without depicting the body directly — how matter itself begins to feel alive.

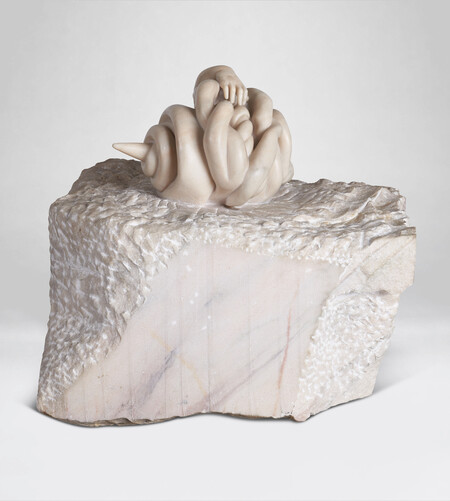

Nature Study, 1986 — Louise Bourgeois

In Nature Study, cold pink marble turns into flesh. Bourgeois makes the stone appear soft and tender by placing a twisted mass atop a rougher surface. The sculpture resembles a snail shaped from a hand twisting onto itself.

The work holds a tension between the inner and the outer: the natural structure of the marble remains visible, yet it is shaped by the artist into something with human traits. This creates the impression of a living being without a clearly defined body; a single hand and its spiraling movement are enough for the viewer to perceive it as corporeal and to understand the sensation of being curled in on oneself.

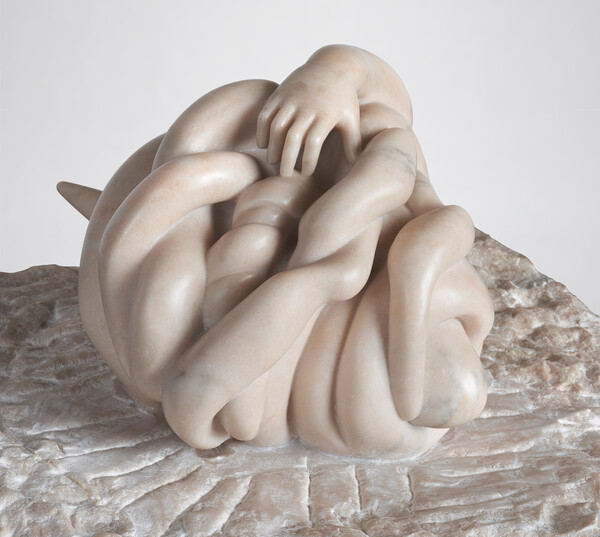

Couple, 2002 // The Couple 2007-2009 — Louise Bourgeois

In the two works titled Couple, the body is depicted differently but becomes an image of dependency and attachment. Two bodies, locked in endless embrace, hang suspended in the air, balancing between heaviness and lightness, merging and simply coexisting. In the soft pink fabric version, the warmth of textile evokes the familiarity of skin.

In the aluminum Couple, the body loses its softness and becomes a polished cast cocoon. The material is cold, yet the form preserves the same tension — the intertwining, the impossibility of separation. Bourgeois translates emotional states into physical form: closeness becomes structure, dependency becomes shape. The body loses individuality but gains a new unity, becoming a symbol of an inseparable human experience.

«Lange eenzame man», 2010 // «Arcangelo glassdome III», 2023 — Berlinde De Bruyckere

De Bruyckere creates bodies that appear almost too alive to be wax sculptures. Her works sit on the boundary between the sacred and the corporeal, as though religious iconography merged with an anatomical study. High Lonely Man — an elongated figure — seems at once sleeping, dying, decomposing, and frozen in a moment of bodily transformation.

The artist deliberately conceals faces, replacing individuality with universality, allowing the body to speak for itself. Blankets, coverings, and skin become thresholds between interiority and exposure, between vulnerability and comfort. In Archangel in a Glass Dome III, this effect intensifies: the legs sealed under glass are perceived as a relic. Berlinde De Bruyckere’s sculptures remind us that fragility can be monumental.

On the Eve, 2013 // When Everyday Was Thursday, 2010 — Francesco Albano

In Albano’s sculptures, the body seems to dissolve into its own shell. Forms sag, stretch, and flatten, as if the skin has separated from what once filled it. These images suggest bodies without support, without a center, existing in a state of collapse.

Albano does not depict suffering but a physical manifestation of inner fracture. His figures lack faces, gender, or age, yet their folds and drooping contours express human vulnerability. Here, skin becomes a material of memory — it holds imprints and traces of life, though life itself has left. The sculptures resemble skins shed from the body, or shells that contain only the echo of presence.

In his work, the body stops being an image of a person and becomes the matter of experience — compressed, thinned, yet still responsive.

Across all these works, the body ceases to be a stable form and becomes a process of change. It is fluid, soft, compressible, decaying, yet still sensorial. The artists show the body not as a representation of a human but as the material of experience — a substance capable of storing memory of life and of touch, which explains its facelessness. Here, the living and the non-living merge: fabric and marble, wax and aluminum, skin and air become equal mediums of corporeality. The body exists not as an object but as a state — mutable.

The Body as Object

Another mode of the body’s presence is its consideration as a thing, an object, a material, a surface. Artists work with imitations of skin, organs, and traces of life, turning the corporeal into an object of observation and reflection.

From Alina Szapocznikow’s lamps to the silicone works of Maayan Sophia Weinstub and the sculptures of Holly Hendry, the body becomes an artifact that preserves the memory of the living. In these works, the viewer encounters a paradox: the non-living evokes a sense of closeness, and the artificial conveys vulnerability. This is where the effect of phantom corporeality arises—contact that happens not through skin, but through visual and emotional sensation.

Lamp, 1967 // Lamp, 1970 — Alina Szapocznikow

In her lamps, Szapocznikow fuses the body with the mechanics of an object. Cast body parts initially resemble abstract color patches or plant-like forms transformed into sources of light. She literally turns the body into a functional object, yet this gesture does not dehumanize; instead, it reveals the body as part of the environment, part of nature.

Dessert III, 1971 // Petite Dessert I, 1970–1971 — Alina Szapocznikow

In the Desserts series, the body becomes an edible image—a metaphor of desire and consumption. Body fragments, reminiscent of marshmallow or meringue, appear appetizing at first, and then, once recognized as human parts served on plates, evoke unease. These «treats» provoke an almost physical reaction through their vivid realism. Szapocznikow exposes the duality of our relationship to the body—between pleasure and fragmentation. Having experienced illness and the awareness of her own mortality, she materializes the anxiety of corporeal existence, preserving it in the form of seduction and irony.

Objects, 2021 — Manuela Benaim

Benaim created a mirror whose surface is cast from an armpit—a part of the body usually concealed. The embedded hair and texture of skin transform the mirror into a living surface in which the reflection is not an idealized image, but the reality of the body itself.

She shows how an item meant as a tool of self-perception becomes a boundary between the real and the imagined body. The mirror does not reflect beauty—it reflects doubt, vulnerability, and imposed norms. Through merging the intimate with the utilitarian, Benaim collapses the distance between body and object, turning the body into a material that looks back.

Bed, 2022 — Maayan Sophia Weinstub

Weinstub’s work is a bed whose sheets are replaced with skin. The surface appears alive yet is marked by bruises and traces of pain. The artist transforms a familiar symbol of rest and comfort into a site of vulnerability and suffering.

The work speaks of trauma hidden within the everyday—of how violence can occur precisely where safety is expected. The body is absent, but its imprint is palpable in the material, in the marks, in the damage. This skin-bed becomes an image of the body’s memory, which retains pain longer than the mind.

The piece resists neutral contemplation: the viewer feels as if intruding into someone else’s intimate space, becoming a witness to what has been endured.

Let There Be Light — Breathing Bulbs Installation, 2024 — Maayan Sophia Weinstub

In this installation, Weinstub brings together light and breath—two symbols of life. Elastic bulbs inflate and deflate, mimicking human breathing.

She merges technique with the organic, drawing a parallel between the human body and a mechanism. The bulbs breathe, but artificially; they live, yet without a body. This synthetic rhythm is both soothing and unsettling, as we recognize our own fragility within it.

Weinstub creates a poetic image of artificial life. Watching the movement of light elicits a physiological response, as if the viewer begins to breathe in sync.

Gum Souls, 2018 — Holly Hendry

Gum Souls, 2018 — Holly Hendry

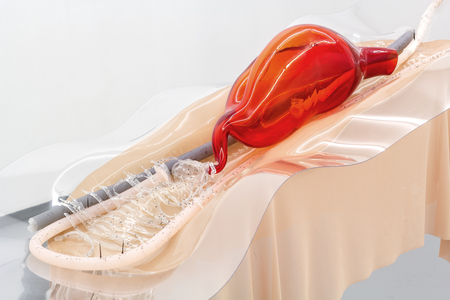

In Gum Souls, bodies appear as slices, diagrams, and fragments of anatomy merged with mechanical elements. Flat reliefs made of pigmented plaster and cement recall medical illustrations and the insides of toys.

Hendry presents another type of corporeality—mechanized yet not lifeless. Her Gum Souls are hybrids of human and machine, both ironic and unsettling. Plaster, metal, and plastic emphasize the synthetic nature of the contemporary body, dependent on technology and infrastructure.

She literally opens up the architecture of the body, revealing that beneath the skin lie no longer muscles but wires, pipes, seams. This is the body of the 21st century—integrated into systems yet still capable of feeling.

Notes to Self, 2024 — Holly Hendry

In Notes to Self, Hendry connects the mundane space of the office with the inner world of the body. Sheets of paper pinned to the wall morph into biological forms fused with bodily materials. This metaphor of to-do lists and reminders becomes an image of mental and physical exhaustion, where the body dissolves into informational noise.

Using glass, metal, ceramics, bronze, and paper, Hendry shows how internal processes—breathing, blushing, digestion—project themselves outward. The body becomes dispersed in space, and its presence phantom-like: we see not a person but the traces of a life, a system of signals and reactions. This merging of mental and physical, living and material, creates the sense that the body «speaks» through things.

The Exhaust’d, 2023 // Watermarks, 2024 — Holly Hendry

In The Exhaust’d, the body and machine merge into a single respiratory system. Metal pipes, glass forms, and a cast-metal ear create a complex structure in which air, sound, and energy circulate. Hendry equates car exhaust, breathing, and hearing—different forms of exchange between inside and outside.

Material becomes a medium of sensation. The work is constructed like an anatomical maze where the mechanical and organic fuse. It is a phantom reconstruction of processes. The body exists as function, movement, circulation—no longer anatomical but conceptual.

In Watermarks, Hendry continues this idea. She turns the façade of a museum into a body with internal circulation—a network of channels, pipes, and systems reminiscent of human anatomy. In its transparent vitrines, the architecture seems to pulse, as if revealing its inner organs. Hendry merges the architectural, the natural, and the anatomical, creating the feeling that even a building breathes, flows, and senses.

The motif of water strengthens the association with liquid as the basis of life: currents, tears, blood, ocean waves. Water becomes a metaphor for corporeality, dissolving the boundaries between the living and the non-living, the human and the infrastructural. This work embodies the idea of the phantom body—a body that does not exist literally yet is felt through space, material, and metaphor. The sculptures, resembling pipes and organs, do not imitate a person but evoke a physical response, as though we are glimpsing a cross-section of our own body. Hendry turns the artificial into the living, architecture into an organism, and observation into sensory participation.

In works where the body is presented as an object, it becomes a material carrier of memory, emotion, and experience. The body turns into a thing yet does not lose its human essence—on the contrary, it becomes even more present through the object.

From Szapocznikow’s lamps to Hendry’s mechanical systems, the body becomes architecture, instrument, and surface through which the act of existence becomes visible. The object becomes an extension of the living.

Аморфное тело

Здесь тело теряет очертания, превращаясь в субстанцию, не имеющую формы, пола и границ. Оно тянется, расплывается, соединяет органическое и технологическое. Это тела будущего: гибридные, синтетические, чувственные.

Ханна Леви и дуэт Pakui Hardware исследуют, как искусственные материалы могут воспроизводить ощущения живого. Их скульптуры кажутся влажными, мягкими, дышащими, хотя сделаны из силикона, металла и пластика.

Аморфное тело — это метафора фантомной тактильности: оно не нуждается в прикосновении, потому что само его вызывает.

«Без названия», 2024 // «Без названия», 2020 — Ханна Леви

В своих безымянных работах Леви создает гибриды телесного и утилитарного. Холодные металлические конструкции напоминают поручни, протезы, элементы мебели — все то, что поддерживает тело, когда оно ослабевает. Но в ее исполнении они в диалоге с силиконовой «кожей», полупрозрачной, влажной, будто живой.

Эти формы кажутся функциональными, но бесполезны: они не помогают, а путают, не поддерживают, а ставят под сомнение саму идею поддержки. Художница словно показывает, что любое тело — временно, что любой механизм, созданный для его защиты, со временем теряет смысл.

В этом столкновении искусственного и живого рождается новое ощущение телесности — когда прикоснуться можно, но не хочется, когда кожа становится поверхностью опыта.

«Без названия», 2023 // «Без названия», выставка «Подвесной пикник», 2020 — Ханна Леви

В работах, представленных на выставке «Подвесной пикник», Ханна Леви превращает предметы дизайна, люстры, шезлонги, кронштейны, в странные, гибкие тела. Металл изгибается, словно мышцы, а силиконовые детали напоминают кожу, растянутую, полупрозрачную, с порами и морщинами.

В этой серии можно увидеть почти гротескную пародию на декоративность: здесь формы вроде бы функциональны, но каждая из них слишком чувственна, чтобы быть просто вещью.

Леви говорит о современном теле, как о предмете дизайна, обрамленном культурой ухода, фитнеса, эстетики и контроля. Ее материалы, сталь и силикон, соединяют в себе холод и тонкость, превращая искусственное в плоть.

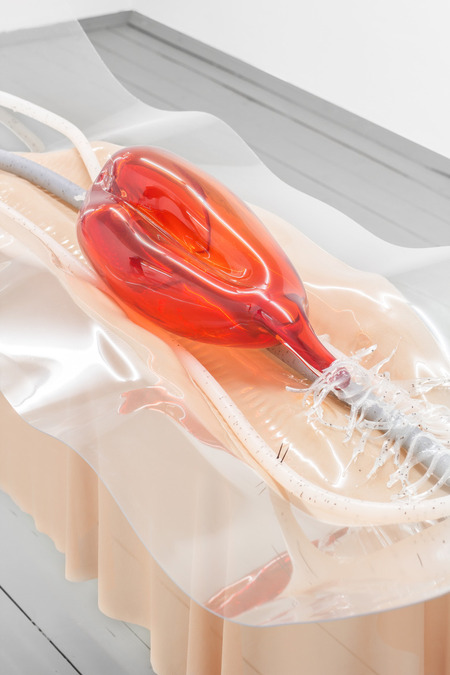

«Возвращение сладости», 2018 — Pakui Hardware

Дуэт Pakui Hardware исследует границы между организмом и машиной. Их скульптуры напоминают внутренние органы, растения, лабораторные сосуды — гибридные формы, где жизнь и технология сплетаются в единый организм.

«Возращение к сладости» обращается к теме метаболизма — как биологического, так и экономического процесса. Скульптуры выглядят словно изнутри тела: прозрачные, текучие, будто наполненные жидкостью. Но это не настоящая биология, а ее синтетическая версия, выведенная из технологических материалов.

В этой аморфной материи исчезает привычная граница между живым и неживым. Художники показывают, как современный человек все больше становится системой, регулируемой и перенастраиваемой, где даже ощущение тела — продукт инженерии.

«Возвращение сладости», 2018 — Pakui Hardware

В этих работах, где тело представлено аморфно, художники исследуют, как современные материалы имитируют живое, создавая иллюзии, показывая форму без формы.

Здесь нет больше различия между человеком и устройством, природой и технологией — есть единая телесная среда, существующая на уровне ощущений.

Это тело не нуждается в присутствии, чтобы быть ощутимым: оно уже существует в пространстве между воображением и материей.

Фрагменты и следы живого

Можно заметить, как в работах все чаще тело перестает быть целым образом — оно распадается на фрагменты, на отдельные жесты, фактуры и материалы, в которых сохраняется его фантомное присутствие. Художники обращаются не к телу как фигуре, а к его остаткам: волосам, коже, шерсти, даже костям. Эти элементы больше не изображают человека напрямую, но продолжают вызывать телесные отклики. В таких работах зритель видит тело через узнавание детали, через ощущение, что эта фактура или даже механика движения когда-то принадлежала живому.

«Лемур», 2020 // «Поглаживание», 2018 — Пфайфер и Кройцер

В дуэте Пфайфер и Кройцер механические дворники от автомобилей медленно двигаются по ворсистым, шерстяным полотнам, словно поглаживая живую шкуру. Это повторяющееся движение одновременно мягкое и тревожное: оно имитирует заботу, ласку, но в исполнении машины лишается эмоциональности.

В их работах фантом тела возникает не в изображении, а в жесте прикосновения, исполненном без участия человека. В этом есть холодная ирония: нежность механизирована, осязание заменено движением прибора. Здесь зритель ощущает телесность не глазами, а телом, которое «узнает» движение как касание. Это опыт симуляции прикосновения — ощущение без тела, жест без субъекта.

«Волосяной дом», 2013 — Джим Шау

В «Домe из волос» Шау возвращается к сказке о Рапунцель, в котором волосы становятся символом зависимости, уязвимости и власти. Перенося этот образ в материальный объект, художник превращает волосы в архитектуру. Материал, привычно ассоциирующийся с телом, становится конструктивным элементом, из которого строится укрытие.

Волосы здесь уже не метафора красоты, а носитель памяти, в котором осталась тень присутствия. Это тело, сведенное к материи, к следу, к субстанции, из которой создается форма.

«Фонтан Наяд», 2021 — Юлия Белова

В своих работах Юлия Белова работает с темами телесности, святости и смерти, создавая пористые, насыщенные деталями структуры, где узнаваемые части тела — ребра, волосы, щупальца — вплетены в массу. В «Фонтане Наяд» синтетические волосы имитируют поток воды, создавая ощущение движения, но застывшего во времени. В другом ее произведении, «Голубая могила», керамические черепа и фарфоровые остатки тел соединяются с мягкими материалами, образуя сплав живого и мертвого, органического и искусственного.

Белова создает гибридные тела, в которых смешаны чувственность и тлен, эмпатия и холодность материала. Здесь тело уже растворено в материи, но остается в виде призрака формы, фантома.

«Голубая могила», 2022 — Юлия Белова

Эти работы объединяет стремление вернуть телесность через след. Если в предыдущих примерах тело действовало: касалось, дышало, взаимодействовало со зрителем, то здесь оно замещено материей, в которой продолжают жить его ритмы.

Это тела без анатомии, где жест, текстура и движение механизма становятся формами фантомного прикосновения.

Если сравнивать работы с фантомными телами и тактильностью с перформансами, то во втором живое тело вызывало эмоциональный отклик и служило медиумом опыта, то сегодня можно увидеть как в части работ отклик переносится на искусственное. Художники создают тела, которые не живут, но ощущаются как живые.

Эти тела существуют на границе узнавания: они могут быть мягкими, хрупкими, полупрозрачными, но всегда вызывают физическую реакцию — желание прикоснуться или отпрянуть. Это и есть новый тип телесности, основанный не на реальном контакте, а на ощущении возможности касания, на воспоминании о теле, которое уже отсутствует.

В этой фантомной форме присутствия телесность становится универсальным языком искусства. Она говорит о хрупкости, уязвимости и стремлении чувствовать. Современные художницы — от Луиз Буржуа и Алины Шапочников до Ханны Леви и Pakui Hardware — не изображают тело, а воссоздают само ощущение его близости, показывая, как искусственное способно вызывать живое.

Тело здесь растворяется в материале, в силиконе, в механизме, в свете лампы или показано только фрагментом. Так рождается новое пространство тактильного восприятия — фантомное, но реальное в отклике. Именно здесь, в этом промежутке между телом и образом, между живым и неживым, современное искусство возвращает способность чувствовать — не через прикосновение, а через узнавание.