Art That Can Be Touched

If performance uses the body as an instrument of interaction between people, then in interactive art contact shifts to the level of the viewer and the object. Here corporeality manifests itself through touch, manipulation, movement, through the physical activation of form. The artist creates, through the object, a situation that is constructed by the viewer in the moment.

This section examines how the encounter between a person and an artificial object forms a new type of tactile experience: from exploratory touch to sensuous and playful engagement. Objects and installations become mediators through which the viewer’s body perceives materials, space, and its own boundaries.

Interactive Art Objects

Interactive objects are built around the possibility of being explored, altered, felt, and touched. Their structure invites movement, bending, and participation, as if the artist were offering the viewer a chance to continue their gesture. A key example is the work of Lygia Clark in the 1960s–1970s, where she proposes various modes of interaction with objects or using them as intermediaries between people, turning the viewer into a participant and the object into a partner in a bodily dialogue.

This line continues in the practices of Rebecca Horn and Haegue Yang, where interaction becomes more than touch — it becomes a way to expand perception and transform the object. The viewer’s body activates the work, but is also altered in return, experiencing new forms of sensitivity.

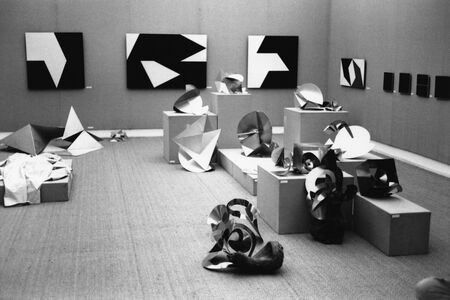

Bicho-Maquete (Creature-Maquette) (320), 1964 — Lygia Clark

Bicho em Si — Pq, 1966 // Pocket Creature (Bicho de Bolso), 1966 — Lygia Clark

Clark’s works frequently dismantle the familiar distance between artwork and viewer. The Bichos series was conceived from the outset as a tactile encounter between the living and the artificial, skin and material. Metal plates connected by hinges transform in the viewer’s hands, acquiring a quality of the living — the ability to shift and change. Clark’s sculptures can be compared to origami: she gives the folded sheet, and each person shapes their own figure. This process turns the viewer into a participant and co-author. The viewer does not simply touch an object, but interprets it, giving it personal meaning and entering into a dialogue between the material and the sensorial.

Sensorial Masks (Máscaras Sensoriais), 1967 — Lygia Clark

In Sensorial Masks, Clark addresses the body directly: the viewer puts on a mask that restricts vision and intensifies tactile sensations through textures and materials. The face — usually an instrument of looking — becomes a surface of perception. The work offers a heightened state of presence, where vision yields to skin. This shift from seeing to touching can be read as a resistance to visual culture, a return of art to the body and to sensorial experience through direct influence on the sensory and physical.

Dialogue Goggles, 1968 — Lygia Clark

Clark’s goggles create a space for interaction: two people look at each other through mirrored lenses in which not the partner, but their own gaze is reflected. Contact emerges at the boundary between what is visible and what is phantom. The interaction becomes a metaphor for how corporeality can be experienced through reflection, indirectly. Through this object, Clark explores how an object can become a mediator between bodies and generate a new vision of looking at oneself in the presence of another.

Finger Gloves, 1972 — Rebecca Horn

Horn’s gloves extend the boundaries of the body, transforming touch into an exploratory gesture. The gloves lengthen the fingers and allow interaction with objects at a distance. The body maintains control, but from afar. This is an experiment with the limits of touch in which the viewer becomes aware not of the object itself, but of the space between the body and the world. Horn invites the viewer to feel not the act of touching an object, but the very possibility for an object to expand one’s tactile and sensory experience.

Sonic Intermediate — Parameters and Unknowns after Hepworth, 2020 // MMCA Hyundai Motor Series: Haegue Yang — O2 & H2O, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2020 — Haegue Yang

In Haegue Yang’s kinetic sound sculptures, the viewer’s interaction with the object becomes a mediator between body and sound. The construction responds to touch, movement, or vibration, producing melodies. Tactility here expands into an acoustic experience: sound becomes a response to the changes initiated by the viewer. Yang’s approach can be compared to the methods of Lygia Clark, whose works «come to life» when the viewer appears. Here, interaction is built on the idea of the viewer influencing the works physically. As a result, without the presence of a person, the objects seem to be placed on pause until their next activation.

Arms, Legs, a Head and Other Everyday Devices (Руки, ноги, голова и другие предметы для повседневного пользования), 2024–2025 — Vsevolod Abazov

Abazov creates works that inherently contain interactivity. His ironic hybrids are tools that have acquired human traits. The artist treats body parts as mechanisms integrated into the material world. The viewer does not touch them directly, but understands their embedded function and logic: people know what it feels like to push a wheelbarrow, can imagine what it is to step on a rake, or to twirl a finger at one’s temple. These objects return touch to the realm of imagination, where the phantom becomes as tangible as the real through an appeal to the viewer’s experience.

Arms, Legs, a Head and Other Everyday Devices (Руки, ноги, голова и другие предметы для повседневного пользования), 2024–2025 — Vsevolod Abazov

In the interactive objects considered here, corporeality manifests through touch, participation, and the physical activation of form. From Lygia Clark’s flexible constructions to Haegue Yang’s kinetic works, artists explore the boundaries between the bodily and the artificial, turning the object into a mediator between sensation and perception. These works create situations in which the viewer experiences art with the body, interacting with what is non-living. Yet over time this direct contact becomes lost: interactive works enter a museum mode of preservation, and the experience of touch becomes inaccessible. Tactility survives only as an idea — a phantom presence, a reminder of the possibility of a bodily dialogue that can no longer occur in action but continues to live in the viewer’s imagination.

Installations Activated by the Viewer

In interactive installations, tactility and the viewer’s presence become the key conditions for the work’s existence. The space responds, reflects, and transforms as long as a body is inside it. In Carsten Höller’s works, the viewer is drawn into an experience of uncertainty and play; in installations by Daniel Rozin or Camille Utterback, the work quite literally comes alive in response to movement; in Kusama’s or Renata Lucas’s projects, interaction turns into a form of co-creating the environment.

These works do not simply require participation — they exist because of it. Contact with the viewer becomes part of their structure, and the very act of touch becomes an artistic gesture through which art reclaims its physical dimension.

Mirror Carousel, 2005 // Golden Mirror Carousel, 2014 — Carsten Höller

Höller’s carousels refer to the childhood experience of spinning and losing balance, but transpose it into the sterile space of the museum. The reflective surface, the slowed movement, the dimmed light — the viewer finds themselves inside a mechanism where the usual logic of perception is disrupted. The carousel becomes an optical and bodily experiment: movement becomes an act of observing one’s own state. As in many of Höller’s works, they create a situation of voluntary disorientation, where the body becomes an instrument of inquiry, and the participant tests the boundaries of balance and control, becoming part of a rotating environment in which one is prompted to observe oneself and others.

Test Site, 2007 — Carsten Höller

In Test Site, Höller turns the museum into a playground. Huge metal slide-tubes penetrate the building, inviting viewers to descend several floors. This gesture is not merely an attraction but an experience of trusting one’s body and examining perception at the moment of losing control. Höller, like an entomologist, uses art as a laboratory of human reactions. Sliding down, a person crosses the boundary between fear and pleasure, between the public and the private. The museum space ceases to be a zone of contemplation — it becomes an arena for a bodily experiment, where movement replaces observation and the body becomes the primary tool of perception.

The Florence Experiment, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, 2018 — Carsten Höller

In The Florence Experiment, the artist connects a human and a plant within a single ecosystem of experience. As the viewer slides down the curved tube, they hold a small plant strapped to their chest — their «companion» in this movement. After the descent, scientists analyze the plant’s condition, studying the influence of human emotions on a living organism. Here, art becomes a field for scientific experimentation, and the person — a subject of observation. Höller investigates the interrelation of the living and the artificial, where interaction is not so much visual as sensory, grounded in bodily response. This project makes the experience itself visible — the sensation of falling, fear, tension, exhilaration — shared by the person and the plant united in one motion.

Dice, 2014 — Carsten Höller

The installation Dice continues Höller’s exploration. The viewer is offered a space of chance, where interaction is built on unpredictability. Like the artist’s other works, it balances between play and inquiry: each attempt at participation is a test of perception and inner balance. Höller constructs situations in which a person becomes a participant in an experiment on themselves. Interaction with his objects requires trust in one’s body and openness to uncertainty and awkwardness — a state in which sensation replaces knowledge.

Pom Pon Mirror, 2015 // Penguin Mirror, 2015 — Daniel Rozin

Rozin’s installations are activated by the viewer’s movement: fluffy pompons and soft toy penguins respond in sync to one’s presence, assembling themselves into a reflection. The work exists only when a person is nearby — it quite literally «comes alive» in response to the viewer. The mirror stops being just a surface and becomes a creature that breathes in the rhythm of presence. Through this gesture, Rozin connects the digital and the bodily, creating a phantom tactility — a touch replaced by a visual reaction yet still felt by the body. The viewer witnesses how their image emerges from movement and becomes a spectator of their own presence.

The Obliteration Room, 2002 — Yayoi Kusama

In Kusama’s space, the viewer is given the ability to transform the environment. Out of sterile whiteness, later covered with countless colorful dots, a new collective visual organism emerges. Each sticker is an act of participation, a gesture of touch through which the artist shares authorship with the public. Here, corporeality lies not in physical contact but in the very idea of the trace: touch becomes color, and interaction becomes an endless layering of others’ gestures. Kusama creates an environment where the boundaries between individual and collective disappear, and touch becomes a form of shared memory.

Slip (Falha), 2003/2024 // Artwork (Horse’s Head and Tail) (Kunst-werke (Cabeça e cauda de cavalo)), 2010/2024 — Renata Lucas

Renata Lucas works with space as a mutable material. In Slip, viewers can lift and reposition floor panels, shifting the room’s configuration. In Artwork (Horse’s Head and Tail), a rotating platform — half flooring, half actual soil — invites people to turn it. As the platform moves, fragments of earth are carried across the white museum space, dirtying it.

These gestures require physical effort and therefore bodily participation. Space becomes flexible, dependent on human action. Lucas invites viewers to reconstruct the environment, turning them into architects of the moment. In her installations, the body feels resistance and weight, bringing back into art the sense of contact with materiality and the mutability of the world.

Thus, in interactive installations, corporeality unfolds in two directions: some works respond to presence and movement, creating a phantom reflection of the viewer’s body (Rozin, Kusama), while others require physical effort, force, or spatial interaction, engaging the viewer bodily (Höller, Lucas). In both cases, the viewer becomes an essential element of the work. These pieces exist only in the moment of contact, when the body activates the space and the space responds to the body. Through this exchange, art takes on a temporary, living character — it «turns on» only in the presence of a person.

Arms, Legs, a Head and Other Everyday Devices (Руки, ноги, голова и другие предметы для повседневного пользования), 2025, 2025, Ruarts Foundation — Vsevolod Abazov

These objects and installations show how corporeality in art extends beyond human-to-human contact. Here, touch becomes an investigative gesture: the viewer touches, moves, activates — and thus completes the work. The body participates in an experience constructed by the artist, becoming a mediator between the human and the object.

In interactive objects, contact remains specific and localized in action. But in spatial installations, as in the works of Kusama, Höller, Rozin, or Renata Lucas, tactility takes on a different scale. It becomes not a moment but a state: the viewer enters, moves within, and feels themselves as part of a changing environment. Here, touch dissolves into space, turning into a form of presence.

Thus, art ceases to be an object and becomes a living system existing only in dialogue with the viewer. And yet, with time, this interaction also begins to shift from real to imagined, from touch to sensation — as in the works of Lygia Clark or Rebecca Horn — driven by the desire to preserve the objects. Where physical contact becomes impossible, what remains is the memory of it: a phantom sense of presence that arises without touching. This boundary between the living and the artificial, between action and its memory, opens the transition to the next mode — where the body no longer touches, yet still feels, seeking connection with the world by encountering another body, but an artificial one.