Performance and Bodily Interaction

Performance is one of the most direct spaces for physical contact in art. Here, the body becomes a medium, and interaction becomes an outcome. Performance makes visible the initial point of this research: the moment when touch is still real and significant, when the boundary between artist and viewer is drawn not by a screen but by the body itself.

In the 1960s–70s, corporeal practices became a language of expression. Artists used their own bodies as instruments of protest and empathy, treating contact as a form of trust and risk.

This section traces how performance reshapes the very idea of presence: from the interaction of bodies within a shared space to the interaction of perceptions, to an experience that can exist without touch. The division into two subsections reflects this shift — from the viewer-participant directly involved in the action to the viewer-observer, whose participation becomes mediated, hybrid, and phantom-like.

Performer and Viewer-Participant

Using the body as a medium can be a provocative gesture aimed at exposing boundaries — physical, social, psychological. Here, contact becomes an experience of trust and vulnerability unfolding in real time.

The viewer enters the action as a co-author: the outcome of the performance depends on their reaction, choice, and presence. In such practices, corporeality becomes a method for exploring relationships between power and submission, desire and fear, the body and the gaze. Physical involvement dismantles the habitual distance between artist and audience, turning the performance into a moment-to-moment construction of experience for everyone involved. In this interaction, the body is not an object but a mediator of dialogue, where meaning emerges through touch.

Cut Piece, 1964 —Yoko Ono

In Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, the artist invites viewers to cut pieces from her clothing. It is a gesture of vulnerability and trust, in which she literally hands control to the audience, opening questions of power, aggression, boundaries, and consent. Each movement of the scissors becomes an act of co-participation: the viewer turns into a performer, while the performance itself becomes a mirror of social relations.

This work establishes a key line of inquiry: bodily interaction as an exchange of power. It turns the viewer into a co-author but also confronts them with a moral choice — how far they are willing to go. This shared experience makes Cut Piece an example of corporeal art in which the boundary of the body becomes an entry point into conversations about responsibility and empathy.

TAPP und TASTKINO (TAP and TOUCH CINEMA), 1968/1989 — Valie Export

Valie Export’s TAPP und TASTKINO (TAP and TOUCH CINEMA) offers a radical response to the male gaze in culture and media. Wearing a box-cinema over her chest, the artist invites viewers to «watch a film» with their hands. This paradox becomes a refusal to occupy the role of the object: Export reclaims control over her body, turning touch into an act of conscious choice.

Here, contact becomes a tool for exposing the mechanisms that have trained the viewer into passive observation. The performance destabilizes the division between seeing and touching, between the intimate and the public, between body and screen. It is a corporeal statement on the power of the gaze and on a woman’s right to her own body, where the viewer, by literally touching, confronts the fact of their own involvement.

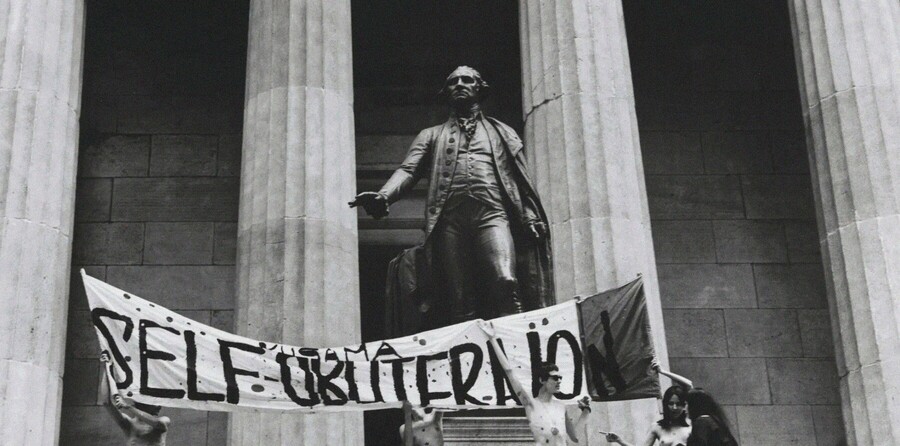

The Anatomic Explosion, New York, 1968 — Yayoi Kusama, Harry Shunk, János Kender

In Yayoi Kusama’s Anatomic Explosion, the artist covers naked bodies with polka dots on the streets of New York. The work is simultaneously an anti-war action and a bodily protest against militarism and capitalist structures. The body becomes a political tool — a living slogan embodying peace and vulnerability.

Unlike more intimate performances of the time, Anatomic Explosion addresses a random public. The viewer is drawn into a collective situation, into a chaotic community of bodies. Corporeality becomes a language of resistance, and the repetitive dots — a symbol of unity and equality. The work shows how the body in art can be not only vulnerable but also a utopian space capable of generating empathy and protest at once.

Imponderabilia, 1977 — Marina Abramović, Ulay

In Imponderabilia, Marina Abramović and Ulay force the viewer to pass between their naked bodies, choosing whom to face. Contact is inevitable but not imposed. This is an experiment in the boundaries of the intimate and the social, where the performers’ bodies become the architecture of experience. Their stillness hands all initiative to the audience, yet it is through this non-action that the encounter occurs. Corporeality becomes a space of choice, revealing each participant’s internal boundaries.

The Artist Is Present, 2010 — Marina Abramović

In The Artist Is Present, bodily interaction is reduced to presence. Abramović sits across from the viewer, without movement or speech. The gaze becomes a form of touch; the viewer is no longer a participant in an action but a participant in a state. The performance demonstrates how corporeality can exist without physical contact.

This work marks both a shift in Abramović’s practice and a broader cultural shift — from bodily interaction to emotional interaction. The title underscores the moment with quiet irony: the artist is present, offering a new form of closeness — phantom closeness. It is a transition to the viewer-observer, where touch is replaced by attention, and participation becomes an inner experience.

Taken together, these performances from the 1960s to the 2010s illustrate a gradual transition from real physical interaction to more phantom forms of presence. The body becomes a field for exploring trust, vulnerability, and control. From Yoko Ono and Valie Export to Marina Abramović, corporeality ceases to be merely an object and becomes a medium through which contact with the viewer takes place. These practices form a foundation for understanding bodily experience in contemporary art: touch may no longer be physical, yet it always remains a point of contact between the person and the world.

Performer and Viewer-Observer

With the development of digital culture and hybrid perception, performances without the viewer’s physical participation have become significantly more common. When corporeality is no longer the only mode of engagement, the viewer’s attention shifts from participation to observation. Performance no longer requires direct contact: the viewer’s presence becomes visual, turning into a form of co-participation through watching and through documentation (for example, filming on a phone). The artist remains bodily active, while the viewer experiences the interaction indirectly — through distance, the gaze, and contemplation.

This separation does not eliminate connection; corporeality is felt through empathy, tension, attention, rhythm, and gesture. Performance becomes a space of presence, where contact occurs without touch and bodily interaction gives way to sensory and psychological co-participation.

Breathing In/Breathing Out, 1977 — Marina Abramović, Ulay

In Breathing In/Breathing Out, Marina Abramović and Ulay, their mouths locked together, exchange breath until they lose consciousness. Here, contact reveals the limits of the body and the performers’ dependence on one another. The viewer observes an intimate act that gradually transforms into an extreme test.

The performance demonstrates that interaction can take place at a threshold where the line between life and exhaustion becomes artistic material. Within this research, it serves as an example of bodily connection experienced through observation: the viewer cannot intervene but feels the physical tension through empathy and attention.

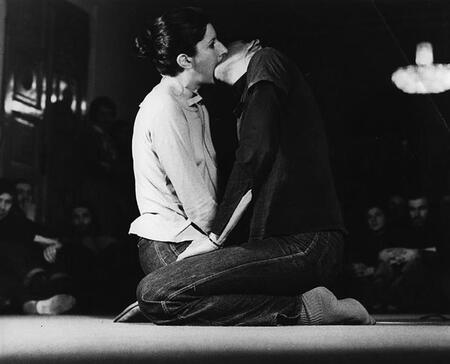

Kiss, 2003, Performance at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2010 — Tino Sehgal

Tino Sehgal’s Kiss transfers classical images of love from painting and sculpture into living movement. A pair of performers slowly shifts positions, reenacting kisses from the history of art — from Rodin to Koons. The viewer becomes a witness to a repetitive, almost ritual action. Sehgal deliberately removes the distance between past and present, art and life, yet maintains a boundary between the performers’ bodies and the audience. Contact becomes an aesthetic experience, like watching paintings come alive: the viewer senses presence but has no right to intervene. Kiss turns a moment of intimacy into a collective act of contemplation, where corporeality and interaction are treated as recurring motifs.

Faust, Venice Biennale, 2017 — Anne Imhof

Faust, Venice Biennale, 2017 — Anne Imhof

In Faust, Anne Imhof creates a multilayered environment of glass and reflections, where performers move among viewers above and below them. Contact here is distanced, occurring through the gaze and through divided space. The viewer finds themselves inside the performance but without the possibility of direct interaction: they watch, record, and move, becoming part of the overall choreography.

Imhof turns observation into a physical state — being a body in the presence of other bodies, separated by a transparent barrier. The performance explores invisible boundaries that, in this case, acquire a literal physical form. It already reflects a shift toward the hybrid attention of the contemporary viewer, who is simultaneously present and recording the event through a screen at a distance.

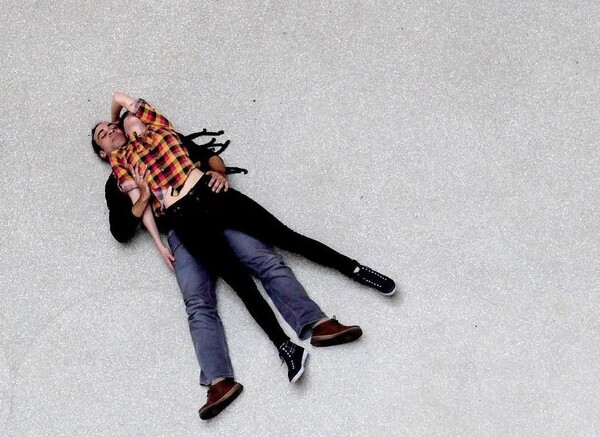

Sun & Sea (Marina), the Lithuanian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2019 — Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, Lina Lapelytė

The opera-performance Sun & Sea (Marina) places the viewer in the position of an observer from above: they watch people sunbathing on an artificial beach. This vantage point seems to strip the body of weight, turning it into an element of a landscape. The viewer becomes a witness to a slow ecological catastrophe taking place in the form of leisure.

Contact between viewer and performers is mediated by space and sound — by the overhead gaze and the rhythm of the songs. People lie, sing, breathe — and in these everyday gestures lies the fragility of contemporary existence. Sun & Sea illustrates the shift from participation to observation.

Sun & Sea (Marina), the Lithuanian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2019 — Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, Lina Lapelytė

Corporeality in performance gradually moves away from direct contact toward presence. The viewer remains engaged, but through empathy, attention, and the act of recording. Engagement becomes phantom co-participation, where the body is sensed through distance.

If in the 1960s–70s the viewer shaped the course of the action — as in the works of Yoko Ono, Valie Export, or Kusama — today they more often become observers, as in the performances of Sehgal or Imhof.

It is noticeable that performances requiring the audience’s physical participation are now far less common. This is directly tied to the transformation of perceptual modes in the digital era. Today, people are accustomed to watching from a distance and documenting rather than participating. By filming a performance on a phone, the viewer takes part in its circulation, fragmenting and reframing the event. Thus, participation changes form: if it was once bodily, body-to-body, it is now mediated — body and device.

This shift is connected to a new perceptual optics described by Claire Bishop, who calls it «distributed attention.» A contemporary person perceives art simultaneously with their body and through the screen, in a space between the real and the digital. This type of attention has become a universal condition for perception in both performance and other art forms, where contact is increasingly replaced by a sense of presence.

The viewer may not be physically near the artist and still be a witness to the action. Performance lives not only in the moment but also in its digital traces, copies, transmissions, and screens. Even in Sun & Sea (Marina) the viewer’s presence is fragmentary — they may come and go, witnessing only part of the action. This reflects the new mode of perception: dispersed, hybrid, distributed between online and offline, instantaneous and deep at once, as Bishop notes.

«Today’s ways of seeing are not just so much dispersed and distributed as incessantly hybrid: both present and mediated, live and online, fleeting and profound, individual and collective — a condition that has only been compounded and intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic.» [Bishop, 2024, p. 6].

This hybridity of attention forms a new type of bodily interaction. The body remains present in performance, but the focus on it is diminished — as in theatre or cinema — and a distinct distance emerges.